By Mary Gartshore The frogs finished singing back in July, and most songbirds have stopped singing—except for year-round residents such as the Northern Cardinal and Carolina Wren. Now, the crickets, katydids, and cicadas are engaged in the third season of song. I will focus on katydids. The natural corridor along the Lynn Valley Trail offers […]

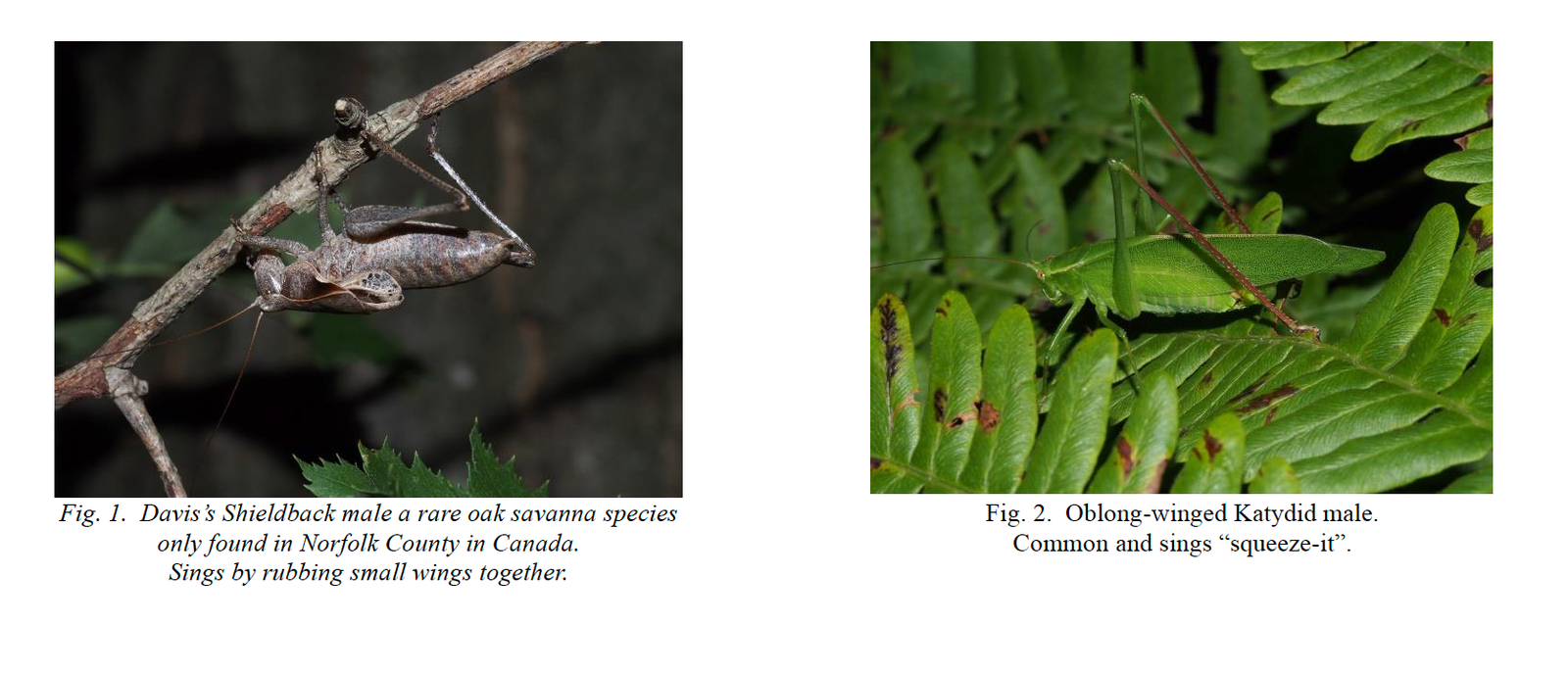

The frogs finished singing back in July, and most songbirds have stopped singing—except for year-round residents such as the Northern Cardinal and Carolina Wren. Now, the crickets, katydids, and cicadas are engaged in the third season of song. I will focus on katydids. The natural corridor along the Lynn Valley Trail offers excellent habitat for all of our singing insects, offering both photography and sound-recording opportunities to visitors. Around July 12, the rare Species-at-Risk flightless Davis’s Shieldback (Fig.1) starts to sing its quiet “suffling” song. It was first discovered in Canada by researcher Tom Freeman from the Canadian National Collection in 1937, on his family farm—now Simcoe’s industrial park on Luscombe Drive.

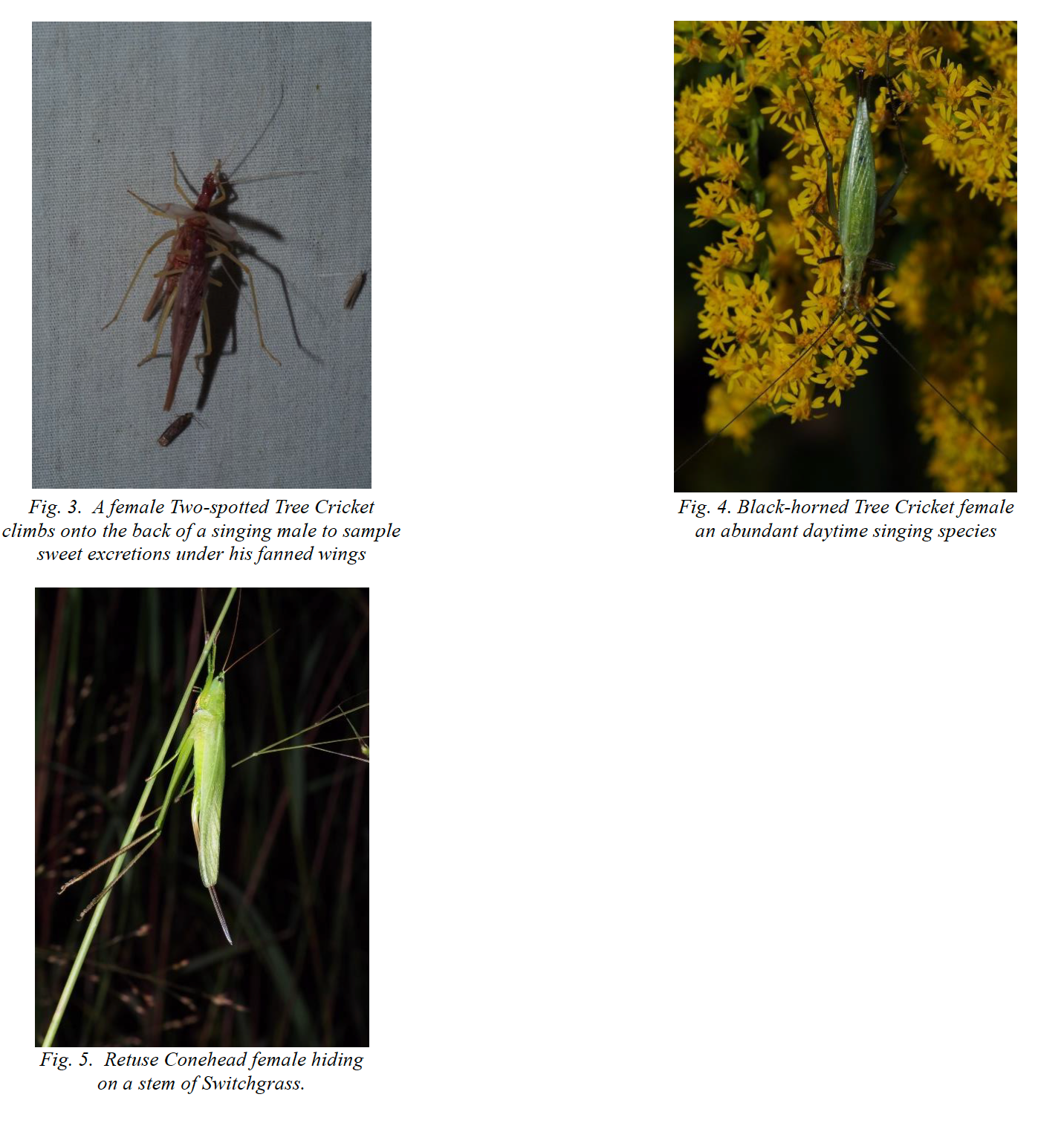

The Oblong-winged Katydid (Fig.2) calls “squeeze-it” at night, often in plain sight atop vegetation. In late July, the first conehead begins to sing, sounding like maracas playing in ditches and meadows. By early August, the southern species Northern True Katydid joins the chorus with its raucous “ret-ret-ret” call, also known locally as the “back-ache bug.” The Northern True Katydid has large rounded wings but cannot fly—instead, its wings act as a sounding chamber. It’s reputed to be the loudest singing insect in North America.

By early September, little tree crickets are in full swing. These include Pine, Snowy, Temperature, Black-horned, Four-spotted, and Two-Spotted species. The Pine Tree Cricket has a clear, sweet tone with no pulses and can be heard during the day in pine plantations. The Snowy Tree Cricket has a low-pitched, 10-second “drrrrrrr.” At night, male Temperature Crickets synchronize a sweet, pulsed “drrr-drrr-drrr…” continuously. Count the number of pulses in 15 seconds and add 40 to estimate the temperature in Fahrenheit. Black-horned and Four-spotted Tree Crickets (Fig.4) are common in open fields, both producing sweet trills. The four spots on the latter are on the front of the lowest segment of each antenna. The Two-Spotted Tree Cricket (Fig.3) is a newcomer—there were no Canadian records until after 1985. By 2013, people were noticing them at porch lights, and now they’re abundant throughout southern Ontario. The unusually warm summer of 2012 may have allowed these insects to colonize further north.

Male tree crickets sing to attract females for mating. They create their songs by holding their wings vertically and rubbing them together. Under their fanned wings are two glands that excrete a sugary drink for arriving females. Females sample the drink before deciding to mate (female on top, male below). Some may simply sample and leave.

In October, the Retuse Conehead (Fig.5) finally matures and begins to buzz softly. It sits on grass stems or Common Ragweed. When approached, it drops into the grass and disappears. There are only a few records around Walsingham, but it’s worth searching elsewhere in southern Ontario. Its larger relative, the Robust Conehead, is a rare prairie species occasionally heard in Ontario. Its buzzing call has a pulse rate of around 240 per second—one of the fastest muscle contractions in any living animal, which has even attracted the attention of nanotechnologists.

A volunteer-driven, non-profit organization dedicated to preserving, protecting, and enhancing the Lynn Valley Trail for everyone to enjoy.